New Media Installation

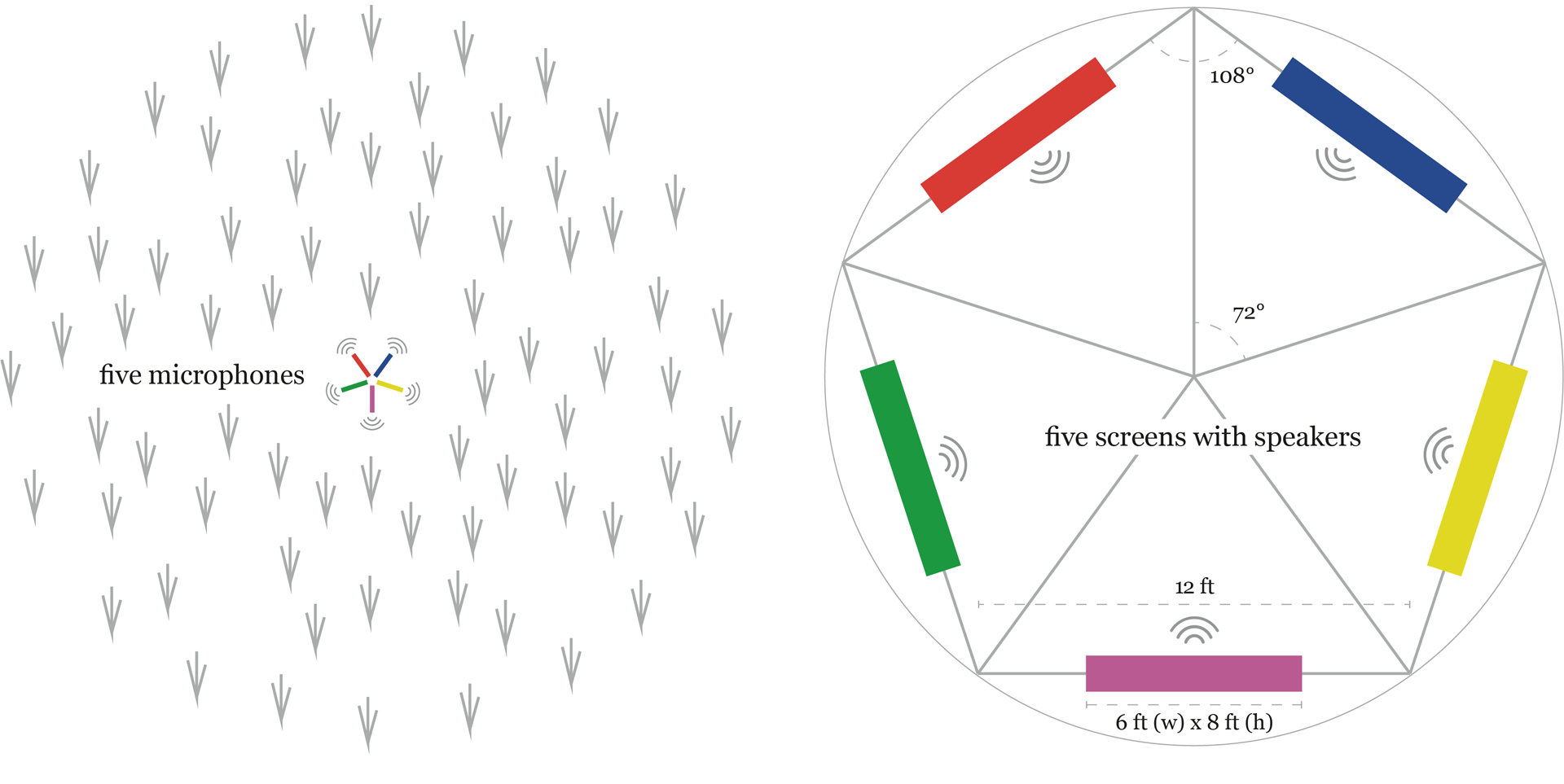

In Earth Week 2016, recording engineer Eric Lamontagne travelled to Saturna Island to help artists Brady Marks and Mark Timmings capture the sounds of the wetland. Equipment to make a five-channel, surround-sound recording was set up on a fallen tree at the centre of the marsh. The array of microphones had the appearance of a technical sculpture or other-worldly probe. It recorded continuously through an entire day and night, collecting approximately one terabyte of data. The recording serves as the foundation for a soundscape-visualization installation.

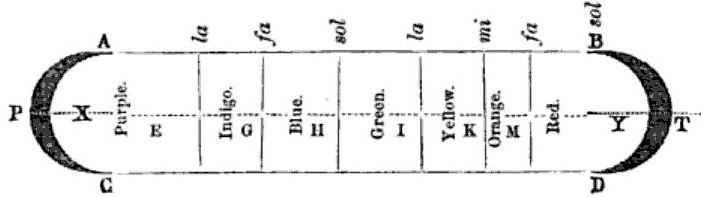

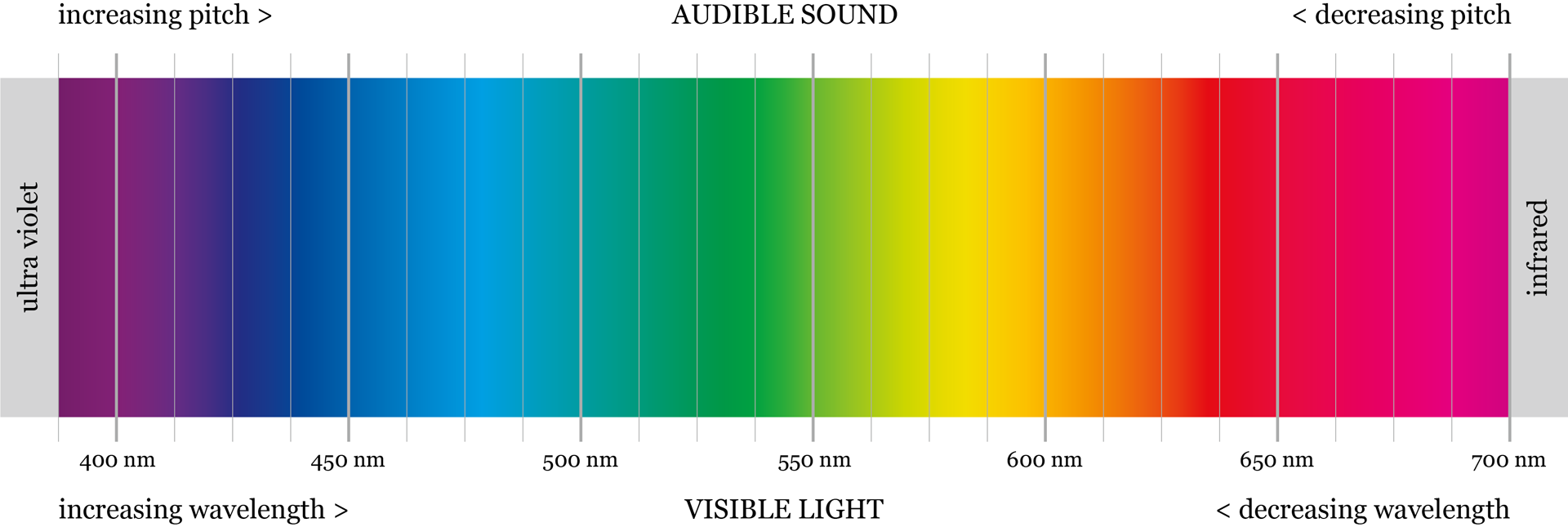

The artists then worked with computer programmer Gabrielle Odowichuk to create an algorithm that transforms sound frequencies from the wetland recording into pure colour fields. This metamorphosis is achieved using an original colour scale based on the visible light spectrum, an exercise that has a long genealogy dating back to Isaac Newton in 1704.

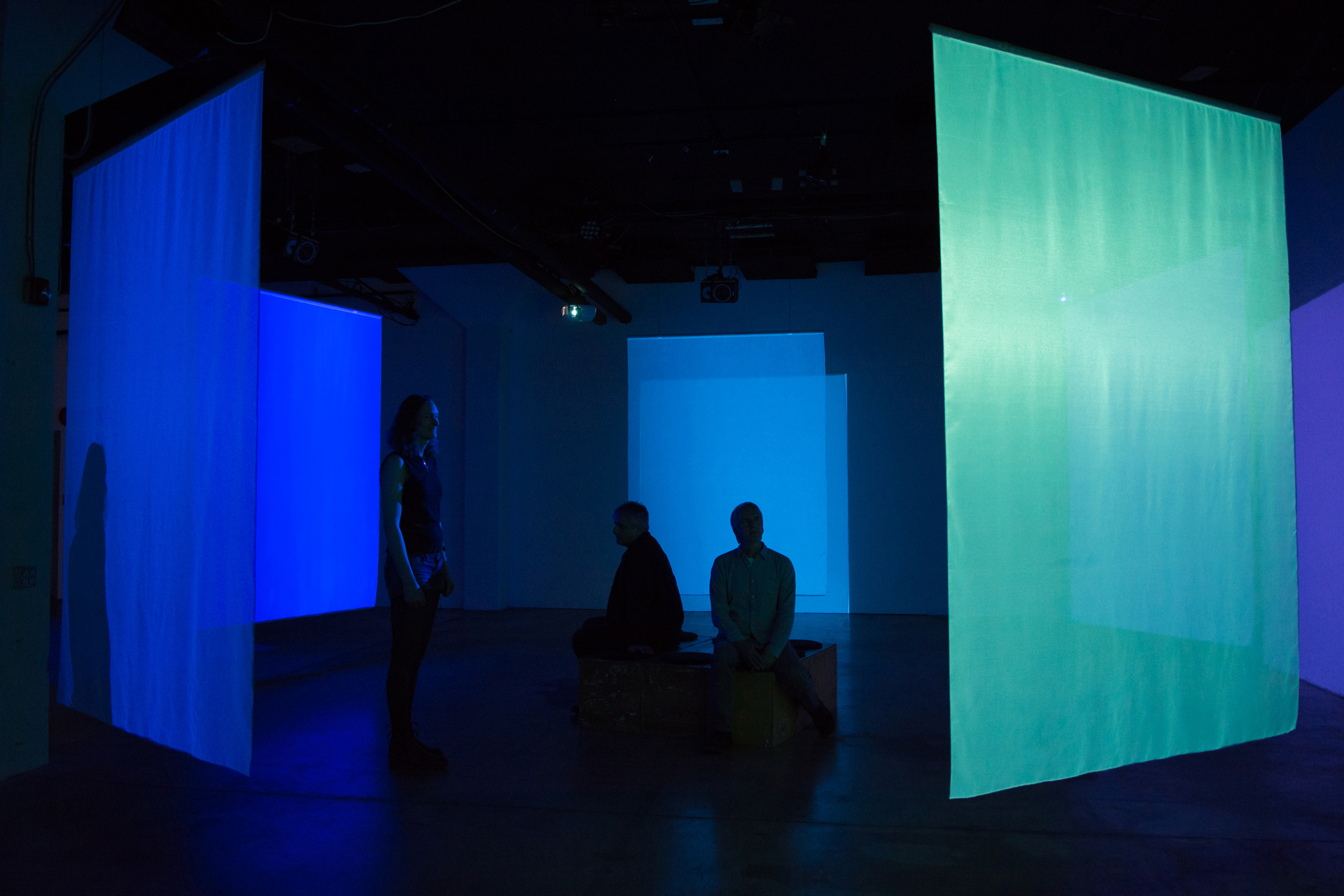

The algorithm creates a seamlessly flowing interface with natural phenomena, conjuring a universe in constant flux. In a gallery setting, the installation consists of five large translucent screens arranged in a pentagon. The screens are spaced to allow the spectator to enter into the centre of the installation. Each screen is paired with a speaker relaying the sound feed from the corresponding directional microphone in the five-channel field recording. This creates a hyperreal environment that attempts to replicate the multi-dimensional experience of the soundscape at the wetland.

Visitors enter the Wetland installation to witness the unpredictable flow of sounds and colours in a strict, yet imperfect, correspondence the technology makes possible. This sculpture of light renders the spontaneity and vital energies of the wetland creatures as the twenty-four-hour sound loop follows a full cycle of the circadian rhythm. Conversations between creatures are transformed into conversations between colours. The audience is immersed in an innovative, synesthetic or cross-sensory experience—a powerful nexus of sound and colour that is unpredictable, spontaneous and sometimes humorous—provoking joy.

The installation explores three critical pathways: soundscape and its importance to environmental awareness; algorithms and their power and fallibility to render natural phenomena; and visualization and its connection to traditions of landscape and colour-field painting.

Soundscape

The conceptual origin of the Wetland installation lies in the work of the World Soundscape Project (WSP), founded in the late 1960s by Canadian composer R. Murray Schafer at Simon Fraser University. The WSP was interested in developing the discipline of an Acoustic Ecology which, as WSP members stated, would “raise public awareness of sound” by “documenting environmental sound and its changing character,” ensuring ultimately that “the human community and its sonic environment [are] in harmony.”

The environmental crises we now face impel us to pay close attention to changing, natural soundscapes. While songbird and frog populations are in rapid decline worldwide, airplane drones and other human-made sounds are on the rise. The presence of noise in the soundscape is a reality that warrants examination. The Wetland installation is an act of bearing witness with ethical and political ramifications. It is a monument (and perhaps, eventually, a memorial) to a very specific site at a very specific time.

Algorithm

The Wetland installation operates as a conceptual machine that is driven by an algorithmic system. The system is ultimately transferable and open-ended, and can be applied to any soundscape at any given time. However, the use of algorithms in the installation is also somewhat cautious and ambivalent. Artist Etienne Zack asks, “are we not at a … junction between what appears to be infinite technological promises and a finite and failing natural world?”

In response to Etienne Zack and following philosopher Martin Heidegger, we seek a free relationship with technology; we hope to avoid its totalizing virtual allure; we seek to give up our authorship to the wetland voices; we engage in minimal representation — an algorithm is employed to translate the soundscape into pure colour fields. However, in engaging the algorithm to create, we also take on the artifacts of the digital sphere. Artifacts such as glitches, temporal shifts and quantization errors are doubly apparent when contrasted with the lush continuous analog domain of the wetland soundscape. Curiously, in embracing the digital, warts and all, we expose its promise of perfection as a lie and witness the fallibility of its translation of the natural phenomena into a representation of the natural phenomena. We remain engaged in this act of translation. In this work, we create a vantage point from which we can confront a shared artifice. Neither we nor our machines can recreate the natural world. We have failed to remove our human voice, and the machines fail to virtually recreate nature. We recognize our shared fallibility; perhaps this is the allure of the machine? That they are like us? Perhaps we don’t see nature’s incompleteness; we view it as perfect and not as a work in progress. With these questions we challenge the audience to discern their tricky position at Zack’s junction. To instill humanism in the infinitely expanding digital universe, algorithms are used in creative and imaginative ways. The Wetland installation is thus designed to promote the involvement of the audience — through immersion, embodiment and cross-sensory experience — in a deeper understanding of their relationship to the natural environment and the implications that this relationship brings.

Through the use of algorithms, notions of authorship are called into question. Despite the impossibility of completely removing our voice from the work, the famous theoretical argument about the “death of the author” acquires a new inflection. In the Wetland installation, we set the initial, conceptual parameters and let the algorithm do all the rest. This is part of the potential inherent in the digital universe. Exploring new technologies, we attempt to erase our presence to the fullest possible extent and let nature speak for itself.

Visualization

The medium is cyberspace and the paintbrush is the microphone. With “visualized sound” comes synesthesia. In an exploration of new technologies, one that continues a long tradition of art-historical practices representing landscape, the Wetland installation both examines and reveals the transformative potential of algorithms. The work offers a new take on reductionism, beginning with field recordings and their realistic representation of a subject, and moving on to a radical process that reduces data to create pure, minimal images of shapes and colours in flux. Remarkably, the outcome is anything but minimalist or sedate; rather, it is an intense reflection of the detailed and vibrant inner complexity of the soundscape.

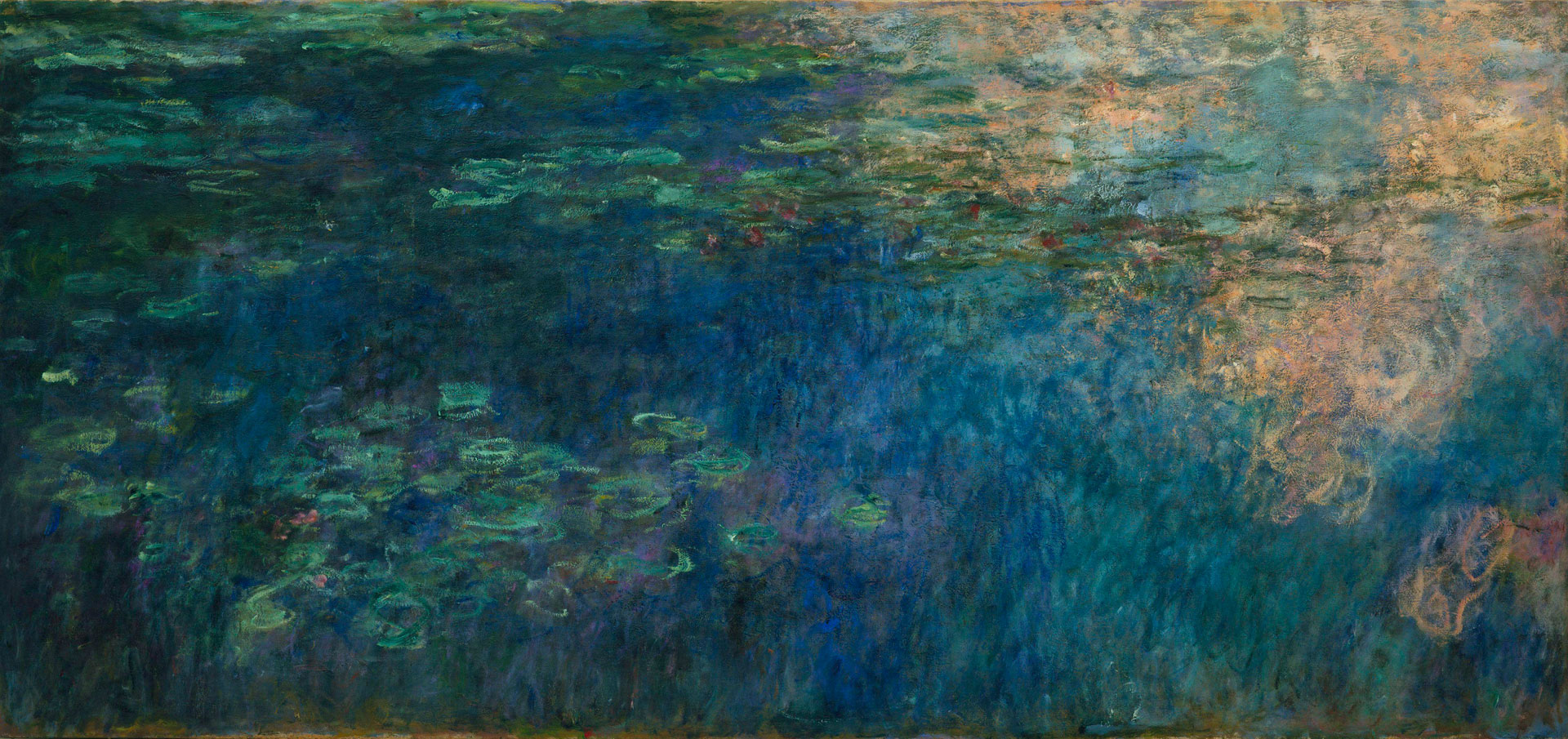

The wetland algorithm produces a colour flow of monochromes and colour fields in continuous transformation. The resulting installation finds an echo in the “Water Lily” paintings (1914–1926) of Claude Monet (1840–1926) which, with their lavish applications of pure colour, are considered to be the origin of monochromes. Frogs and birds are abundant in the wetland recording, providing a sonorous tribute to this series of paintings by Monet. Cross-sensory correspondences in colour and tone can be found between the paintings of Monet and the musical compositions of Debussy.

Like Monet, Mark Rothko (1903–1970)—who drew comparisons between his work and Monet’s “Water Lilies”—produced large-format paintings in series that fill the viewer’s field of vision with expansive applications of colour. On screen, the film-like flow of colours produced by the wetland algorithm bring to mind the optical titillation of the subtly animated colour frames in Rothko’s paintings. Rothko is considered to have broken down the barriers between optics and sound, painting and music. The fourteen large paintings installed in the octagon-shaped Rothko Chapel in Houston have inspired musicians and sound artists to compose works in situ such as Morton Feldman’s Rothko Chapel (1971). Here, sound emerges from the visual realm while the opposite is true of the Wetland installation.

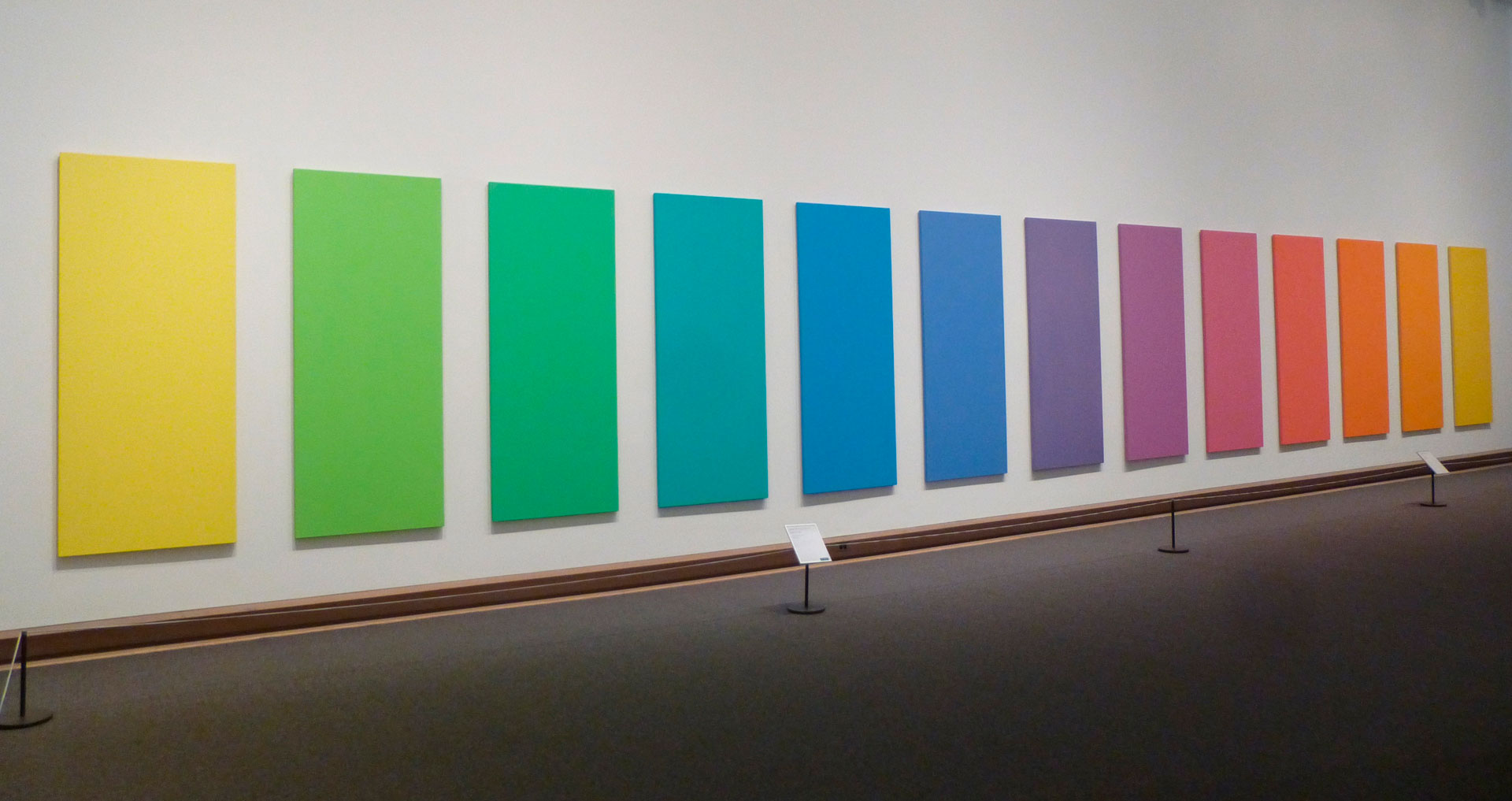

Ellsworth Kelly (1923–2015), another artist influenced by Monet’s “Water Lilies,” also painted large monochromes in series. He engaged extensively with Isaac Newton’s theory of the relationship between light and colour. The screens in the Wetland installation echo the panels in works like Kelly’s Spectrum V (1969). Kelly also produced monochromes, such as Three Panels: Red Yellow Blue II (1965), inspired by the colour of birds he observed in his native New Jersey.

Finally, in reference to the work of the Modernist painter Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage writes of a “painting constantly changing” and of “a poetry of infinite possibilities.” The Wetland installation is a concrete, literal actualization of these words.